Should AI companies pay artists?

featuring opinions from PRS for Music

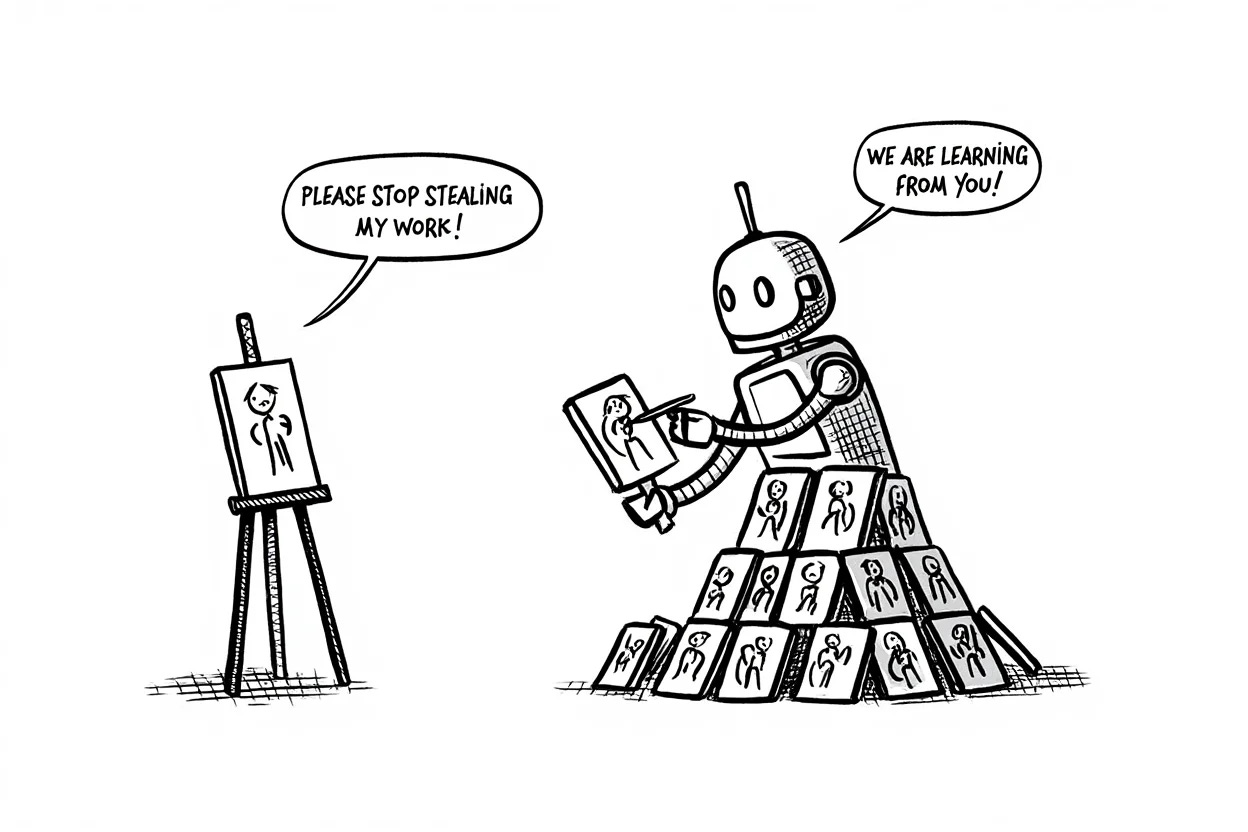

Should AI companies pay artists for training on their work?

Well, that depends on what you mean by should — legally, ethically, or philosophically? Either way, it’s a question I rarely hear at Bay Area networking events. No wonder, of course, questions like this get easily drowned out in the fireworks of progress.

While there are AI startups like Moonvalley or Beatoven that exclusively train on licensed data, the rest of the technosphere does not share the same view. Both OpenAI and Google argue that it should be free to train on copyrighted data. More specifically, Google argues that the current U.S. law can be interpreted to support its claim. OpenAI, on the other hand, raises national security concerns, claiming that copyright laws could cause the U.S. to fall behind in the AI race — since it believes that Chinese AI companies won’t respect copyrights.

Artists clearly disagree, as hundreds of Hollywood figures like Guillermo del Toro and Paul McCartney signed an open letter in protest of OpenAI and Google’s stance. However, the world had long moved past the niceties of open letters, as there has been a series of litigations between copyright holders and AI companies such as

New York Times v. OpenAI (text data)

Getty Images v. Stability AI (image)

Recording Industry Association of America v. Suno AI (music)

There’s clearly a rift between the tech world and the artists, so where do we go from here?

At the inaugural HumanX conference, I had the opportunity to sit down with two key executives from the music industry: Andrea Czapary Martin, CEO of PRS for Music, and John Mottram, Chief Strategy, Communication & Policy Officer. PRS for Music is one of the largest music societies in the world, responsible for collecting and distributing royalties for over 42 million musical works on behalf of 175,000 members — including artists like Billie Eilish, The Beatles, and Charli XCX.

In this blog post, we’ll explore

Perspectives from PRS for Music

The current legal landscape

What the future could look like, legally and ethically

Perspectives from PRS for Music

PRS for Music is the perfect company to speak on this subject. On one hand, it has represented musicians’ interests for over 100 years; on the other hand, it is one of the most tech-forward organizations in the industry. Throughout my conversation with Martin and Mottram, I learned that they are genuinely open to the adoption of AI in creative processes, and they even hosted a panel about Making Music with AI so their members can better understand the potential of this technology.

To PRS for Music, AI is a wonderful tool that unleashes the creativity of musicians and can be their copilot in producing even better work. This is supported by a recent survey conducted by PRS for Music, which showed that ~60% of musicians are considering using AI in the future, while 30% are using it already.

However, despite PRS for Music’s willingness to collaborate with AI companies, the goodwill has not been reciprocated. While AI music companies like Suno AI have publicly admitted that they are actively training on copyrighted music, PRS for Music has never been approached by any AI companies to seek permission.

PRS for Music believes that AI companies should license music for training, and they are not alone. Alongside other key industry organizations like — Motion Picture Association, Getty Images and the Associated Press — PRS for Music is a part of the Creative Rights in AI Coalition, which believes that

AI developers should obtain permission to train on copyrighted data

AI developers should disclose the source of their training data

A robust content licensing market is essential for the growth of both the creative industry and generative AI

While the coalition is advocating for greater collaboration between AI developers and copyright holders, some parties — as we’ve mentioned earlier — are already taking the fight to court.

The current legal landscape

Fair use or over use?

Most of the ongoing legal disputes hinge on the interpretation of fair use, which I went over in my last blog post about the Ghiblification trend.

In general, four key factors guide the conversation around fair use

The Purpose and Character of the Use

The Nature of the Copyrighted Work

The Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Taken

The Effect of the Use Upon the Potential Market

In the case of AI music model training, Suno argued that training is fair use because

The Purpose and Character of the Use: Suno AI used the musical work to train an AI model as opposed to play it in public, which makes it a transformative use.

The Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Taken: While Suno trains on an extensive corpus, very little of the original material appears in the output.

In contrast, the plaintiff — Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) — argues that training is not fair use due to The Effect of the Use Upon the Potential Market, since a flood of AI generated music could severely impact musicians’ livelihoods.

Some argue that fair use, codified in 1976, is overdue for an update, especially given the rapid advancements of AI. In other words, AI has pushed copyright laws into uncharted territories, and the ambiguity of fair use makes it extremely challenging to reach a clear verdict. So, again

Should AI companies pay artists for training on their work?

As we look ahead for the answer, it might benefit us to look around first. After all, both AI and music are global industries, so what do the laws and regulations look like in other regions?

Look around before looking ahead

Let’s examine two examples at opposite ends of the spectrum — Japan and EU.

In 2018, Japan amended its Copyright Act to include Article 30-4, which created a broad exception for the use of copyrighted works for "information analysis" — including AI model training even for commercial purposes. Note that, Article 30-4 does include nuances that limits applications that generates similar work or “unreasonably prejudices the interest of the copyright holders.”

While Japan is much more lenient on AI model trainers, EU is more on the side of the creators. The EU AI Act allows copyright holders to opt out of AI model training, and the extraterritorial reach clause mandates that the opt-out preference must be honored globally as long as

EU data is used

The AI model is deployed within EU

While this seems promising in theory, it’s nearly impossible to prove that a specific song is used in training unless AI companies proactively disclose their data sources. In other words, how can we enforce a law without the ability to reliably detect violations? In response, Mottram smiled and said

The system is very obviously broken at the moment, and all governments need to come together to make it work.

Looking ahead

During the interview, Mottram suggested that the current industry consensus is that the license should not be a one-off purchase. Instead, the license should include a recurring component since, once the musical work is ingested, the AI model can generate music and potentially draw on the original work in perpetuity.

GEMA has recently proposed a licensing model that includes an upfront and recurring fee. However, the recurring component related to subsequent use remains vague, as it is challenging to detect whose work has been used in the AI generation process. PRS for Music did not comment on the GEMA model, but emphasized that AI could be a powerful tool for musicians, and they are keen to work out the difference to ensure the mutual prosperity of AI developers and musicians.

Another proposal advocates for statutory remuneration rights, which allows AI companies to pay a predefined fee to right holders without prior authorization. However, the model lacks a recurring component and it would still require negotiation, as the predefined fee would likely vary from artist to artist.

One model that I’ve been mulling over is inspired by the AI music startup Lemonaide, which offers a library of music models trained by popular producers like KXVI and Mantra. This kind of artist model makes it much easier to track and attribute license, and it even opens the door to MoA (mixture-of-artist) models that could spark new musical styles. In addition, it allows musicians to properly credit the source of their inspiration. In a previous blog post about the AI x music stack, I wrote about my experiments with Suno —

In my 2025 New Year piece, I was stuck for a really long time on one section. Since I was writing this blog, I fed Suno my composition up til that point and asked Suno to extend it. I generated about 20 minutes worth of melodies and in the end found 15 seconds that had the spark. What’s more interesting is that I would never come up with those melodies myself, and deviating from my own creative inertia and toying with the anticipation made this piece much more interesting.

But maybe that 15-second spark came from a real musician somewhere — someone I might have heard in a random coffee shop, a jazz bar, an elevator or just on YouTube, yet there was no way for me to trace back and credit that person.

Outro

We looked around before we looked ahead, but it’s also important to look within.

Law is the lowest bar of our moral standard — just because something’s legal (for now) does not mean it’s right. I do not believe that massive AI training on artists’ work without permission or compensation is right — most artists already make very little, and it is unfair that AI companies are raking in millions at the same time, which would not be possible without the artists that poured hearts and souls into their work.

This is likely a symptom of today’s AI learning paradigm, where massive consumption of data is needed. Yet we all know that you don’t need to hear every song in existence to make music that resonate with the world.

Perhaps a better way forward is by building an AI that actually understands music theory, instead of chewing everything up and regurgitate inspiration as a service.

Progress is good, messy, and can often come at the cost of somebody else. However, as a modern society, we should do our best to address the interest of the affected party. I continue to believe in the potential of AI in creative processes, and I look forward to many more uncomfortable discussions ahead.