Scaling psyops

It's just marketing

Recently, the CIA released two Mandarin ads aimed at recruiting Chinese officials.

Reason to collaborate: to be the master of your own fate (English Dubbed) — targeting senior officials

Reason to collaborate: to create a better future (English Dubbed) — targeting junior officials

What can I say? Those ads are pretty cringe. Besides the content, it just doesn’t feel very professional to be recruiting international spies on a social media platform. There’s clearly a mismatch of the “brand identity” and the “marketing channel,” but I guess anything goes these days if the White House has a Lo-Fi MAGA playlist.

Anyway, I digress. Although the CIA stunt hasn’t gone viral on the Chinese Internet, commentary has started to surface. While most are ridiculing the awkward accent in the ads, Hu Xijin, the former editor-in-chief of the Global Times—a media outlet affiliated with CCP —called the campaign “an action that is almost openly hostile to China.” Hu is more of a clown on the Chinese Internet at this point, but he did make another interesting point — instead of looking at these ads as a sincere olive branch, they are more likely designed to sow distrust within Party ranks by stoking fears of internal espionage.

In other words, this is more of a psyops than a recruiting attempt.

While this is laughably unlikely, it sent me down a rabbit hole into psyops history. Psyops has been around forever, probably since when we first learnt to kill one another — there’s a legend that Alexander the Great commissioned giant armor built for eight-foot-tall “soldiers,” and left them behind to terrify his enemies into thinking that his army had giants.

While psyops can take many forms — from fake giant armors to cringeworthy ads — they all try to tap into basic human instincts like fear, self-preservation, love, and even jealousy. Peering back in psyops history, the constant theme has been scaling the reach of influence on the back of new technologies. As global tensions mount again, where does the battle for hearts and minds go?

Scaling psyops over the air

Scattering fake made-to-order giant armors is hardly scalable for the modern warfare. As time goes on, each leap in technology expanded the reach, impact and creativity of psyops campaigns. If we take a look at the early history of scaling psyops, for a very long time it had been a battle over the airspace.

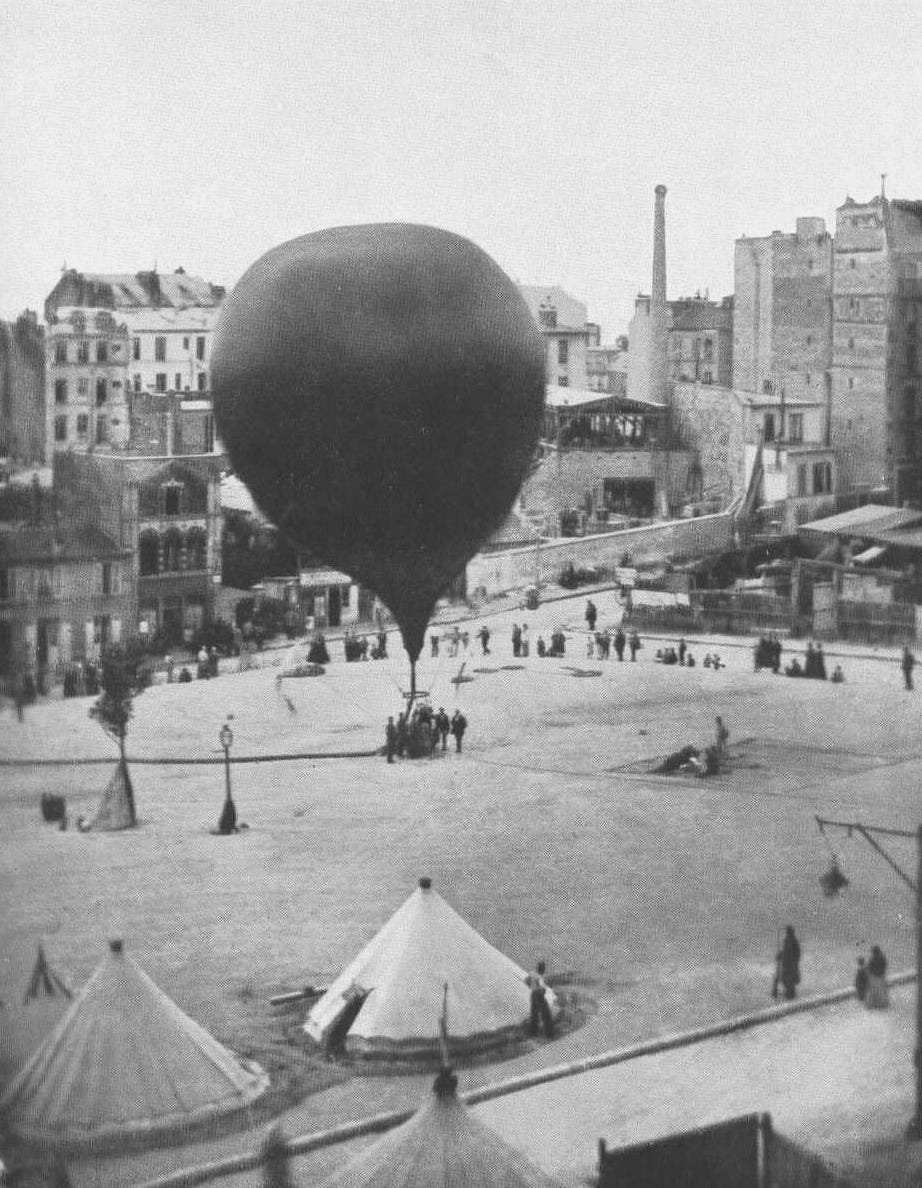

Over the air 1: Hot Air Balloon

One of the earliest examples of using balloons to drop propaganda leaflets was in 1854, when the French tried to persuade Russian soldiers to stay out of the Crimean War. Later, during the 1870 siege of Paris by the Prussians, the French launched 66 unguided balloons over enemy lines carrying 10,000 leaflets, urging German troops to recognize that the French were no longer ruled by emperors and suggested that the needless bloodshed could end if the German simply joined the French.

Over the air 2: Airplane

As aviation technology advanced, more efficient and guided psyops campaigns became possible. The invention of airplanes in the early 20th century turned leaflet drops from a weather-dependent gamble into a somewhat precise tactic. During World Wars I and II, planes became the workhorses of aerial propaganda, scattering millions of leaflets behind enemy lines in a matter of hours. Both the Allies and Axis powers used them extensively to demoralize troops, encourage surrender, and provide instructions for safe defection. The British and Americans even developed specialized leaflet bombs, like the Monroe bomb, which could deliver hundreds of millions of leaflets over enemy territory.

Over the air 3: Sound waves

While planes scaled up psyops by a magnitude, they are still limited by borders, weather and enemy activities. Sound waves do not care. By World War II, propaganda over the airwaves had become a cornerstone of psychological warfare, with both overt and clandestine stations broadcasting propaganda and misinformation.

While loudspeakers blasted on at the edge of conflict, clandestine radio stations were able to penetrate enemy line and often masqueraded as legitimate enemy broadcasts. During Vietnam War, in just 1966 alone, the Air Force dropped over one billion leaflets and broadcasted hundreds of hours of propaganda, which led to the defection of more than 15,000 Viet Cong soldiers.

Scaling psyops over Internet

While airborne tactics defined much of the 20th century’s psychological warfare—from floating pamphlets to booming loudspeakers—psyops continued evolving alongside communication technology. As societies shifted from physical to digital infrastructure, so too did the methods of influence. The rise of the internet didn’t just change how people connected; it redefined the terrain on which psyops could operate. No longer constrained by geography or weather, psyops entered a new phase.

Why email isn’t a good psyops platform

In addition to large scale propaganda happening in the airspace, there were also more creative attempts to slip messages behind enemy lines. One of the most well-known psyops campaigns was Operation Cornflake in WWII. On February 5, 1945, operatives dropped eight mailbags in a bombed German mail train — each one filled with fake letters and newspapers. These counterfeit mailbags were carefully designed to look authentic, complete with real German addresses, legitimate business return addresses, and postage stamps that closely resembled official ones—some subtly altered to show Hitler’s face as a skull.

Creative as it was, it’s extremely hard to scale given all the effort going into forging the materials. So when communication shifted from physical mails to emails, it seemed like psyops would follow too. Email is easy to automate, personalize, and mass-distribute—so why didn’t it become a staple of psychological warfare? You could argue that it’s due to the fact that we haven’t had major scale conflicts that would require a digital campaign since the invention of email in 1971, or you could argue that other social media platforms simply have more reach than email.

However, email is fundamentally flawed for psyops delivery. Spam filters and cybersecurity tools make it challenging for these messages to even reach their targets. Unlike a poster on a wall, a radio broadcast, or even a social media post that can be passively consumed and shared, emails require the recipient to actively open and read them. If you’ve ever been on a GTM team, then you know that many people simply don’t open their emails. Plus, most people are naturally skeptical of unsolicited messages in their inbox—especially from unknown sources—which makes it hard to gain trust or spread influence at scale.

TikTok: The perennial new frontline

This brings us to TikTok—arguably the most potent modern vehicle for influence operations. In fact, one of the key motivations behind the proposed TikTok ban is the platform’s potential to conduct large-scale psyops on U.S. users.

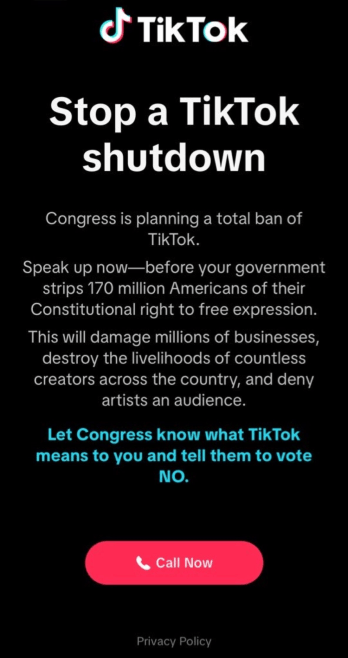

TikTok currently boasts ~170 million active users in the U.S., far surpassing X and on par with Instagram. When it first faced a potential ban, TikTok urged users to contact Congress in protest. The move backfired, obviously. What was meant to feel like civic engagement came off as mass agitation. While there are precedents of companies rallying their users in political matters, TikTok’s ties to the Chinese government made this appeal far more troubling.

If the concern ended there, the threat might be more manageable. In a time of crisis, the U.S. could, in theory, block TikTok at the ISP or CSP level. But psyops is not a one-off risk, as there’s growing evidence of TikTok’s systematic influence operations.

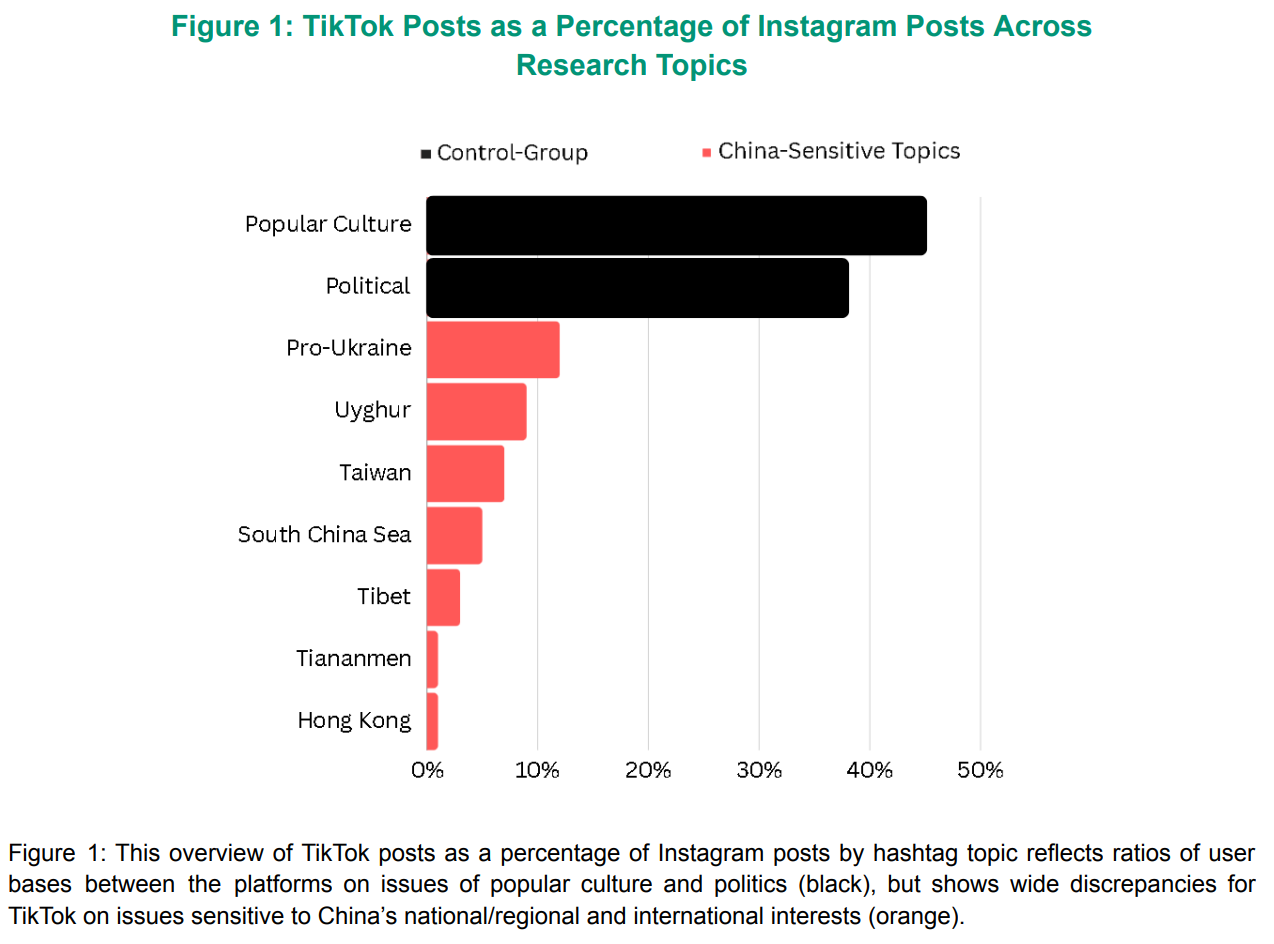

A 2023 paper from Rutgers University’s Network Contagion Research Institute, titled A Tik-Tok-ing Timebomb: How TikTok's Global Platform Anomalies Align with the Chinese, examined how TikTok manipulates content visibility. The study compared the distribution of topics on TikTok with similar content on U.S.-controlled platforms like Instagram, and found that critical content about China is heavily suppressed.

Outro

The battle for our hearts and minds continues—but it no longer floats by balloons or blasts through a speaker. Today, it scrolls through our feed. As global conflict increasingly plays out in the digital realm, psyops is shifting from broad propaganda to more subtle, persistent influence. Future operations may not aim to shock or persuade in obvious ways, but to slowly shape perception through everyday content in our little echo chambers. Platforms like TikTok are only the beginning. As AI-generated content, deepfakes, and hyper-personalized influence campaigns become more accessible, the most effective psyops may not feel like psyops at all—it may just feel like the Internet is working as usual.