CHIPS, It's time to be mature

A memo in response to a policy contest on the rise of Chinese mature node industry

This is a bit of an unusual post, I originally wrote this in response to Noah Smith’s policy competition.

While I was sadly not one of the winners, this was a fun thought experiment.

Lastly, a thank you to the team at the Federation of American Scientist for helping me polish this memo!

Summary

Chips are power, and, for much of the past century, semiconductor technology and production has been largely dominated by the United States and its allies. However, in recent years, China has been rapidly developing its semiconductor industry, thereby increasing its leverage in the global market. Since October of 2022, U.S. policies sought to curb China's advancement in the semiconductor industry, but most of them targeted advanced node production, defined by the CHIPS and Science Act as chips smaller than 28 nm. While recent export controls and other measures have likely slowed China's progress in developing cutting-edge technologies, they have not curbed China's growth in the mature-node sector of chips larger than 28nm.

By the end of 2023, China accounted for approximately 31% of global mature node production, a significant increase from 17% in 2015. Furthermore, China is expanding its manufacturing capacity, with 44 operational fabs and 22 additional ones under construction. In comparison, the U.S. has 24 fabs and 6 under construction, with key allies like South Korea, Japan and Taiwan trailing behind.

Policymakers should recognize that mature nodes are of strategic value as well, as they can be found in both civilian and military hardware such as vehicles, electronics, factories, medical devices. The inability to produce enough mature nodes to meet domestic demand would be devastating, as the 2020-2023 chip shortage previewed.

There are various theories of harm in circulation regarding the motive behind China’s increasing dominance in mature node production. A smart U.S. strategy should soberly assess the potential risks and hedge against potentially dangerous future scenarios.In response, it will require a two pronged approach – a foreign policy that fosters new partnership, specifically India, and domestic policies around stricter export control and defense procurement.

Challenge and Opportunity

There are four primary theories of harm to explain why China’s growing market share in mature node semiconductors could potentially challenge US and global interests:

Dumping

On-shoring

Buying leverage with market share

Cybersecurity warfare

Dumping

The first theory posits that China has been increasing its mature node production through substantial state subsidies to dump overcapacity into the international market, thereby gaining an unfair economic advantage. This strategy is often used to destabilize competing markets and industries by flooding them with cheap products, undermining local production and leading to potential market failures.

The overcapacity in China's semiconductor production is likely due to mistakes in demand forecasting following the COVID-19 supply chain disruptions rather than a deliberate economic strategy. According to the report "Legacy Chip Overcapacity in China: Myth and Reality" by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), it is challenging for foundries to swiftly adjust production lines in response to demand fluctuations, particularly for mature-node productions operating on very thin margins. As a consequence, foundries and customers prefer long-term contracts to secure a specific type of semiconductor, particularly in industries with long product life cycles and stringent quality requirements such as medical devices and automotive applications. Li Ke, vice president of China Center for Information Industry Development’s consulting arm, pointed out that in the past few decades the average company's chip inventory was only 7 days, but now companies generally stock months worth of inventory. Moreover, fabs take 3 - 5 years to build, so the delayed overstocking effect after the initial supply shortage could be misinterpreted as intentional overcapacity.

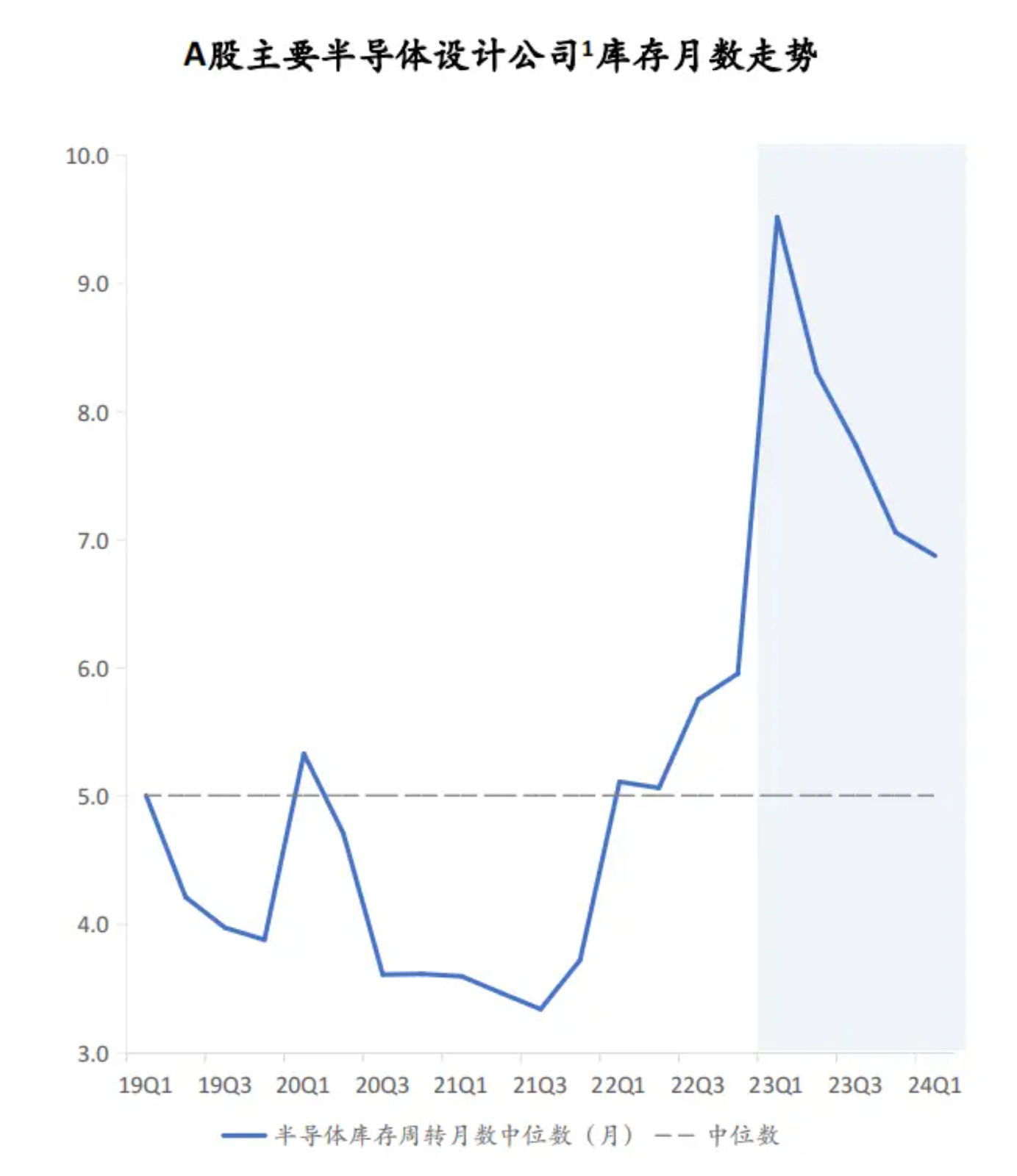

Moreover, since the first quarter of 2024, the utilization rates of most Chinese fabs have normalized. SMIC's utilization rate increased to 80.8%, HuaHong to 91.7%, and Nexchip has been operating at 110% since March 2024. Inventory levels in major Chinese semiconductor companies have significantly declined since the third quarter of 2023, indicating that the perceived overcapacity is being effectively managed.. According to industry reports, the median inventory of 33 representative semiconductor companies listed on the Chinese A-share stock exchange fell from a peak of 9.5 months in the first quarter of 2023 to 6.7 months in the first quarter of 2024.

In other words, it is unlikely that China is intentionally dumping chips as its utilization rate and inventory level are both returning to industry average.

On-shoring

The second theory suggests that China is increasing its mature node production to onshore more elements of the semiconductor lifecycle, from design to full-scale production.

This strategy is clearly articulated in the “Made in China 2025” initiative, which aims to reduce China's reliance on imported chips and on shore production. Data from the Guidelines to Promote National Integrated Circuit Industry Development also indicated the same strategy by setting an aggressive target of 70% localization rate by 2025. From 2018 to 2022, China's chip self-sufficiency rate increased from 5% to 17%, with an estimated 25% self-sufficiency in 2023.

According to the International Semiconductor Industry Association (SEMI), Chinese chip manufacturers' capacity is expected to expand by 12% this year. If the expanding capacity is mostly serving foreign demands, then the on-shoring claim would be weak. However, SMIC has shifted from 60% foreign customer production five years ago to nearly 80% domestic production. Similarly, 80% of Huahong's production is for domestic customers, which indicates a strategic pivot towards meeting internal demand. In other words, China is expanding capacity and redirecting existing capacity in order to serve its domestic demand.

Between 2021 and 2023, China's import volume of semiconductors decreased from 635.5 billion units to 479.6 billion units, while the export volume decreased from 310.7 billion units to 267.8 billion units. This data indicates a strategic emphasis on on-shoring rather than dumping excess production.

Buying Leverage with Market Share

The third theory posits that China is increasing its mature node production to gain market share and subsequently use this dominance as geopolitical leverage. Dependence on Chinese mature node exports could create opportunities for China to coerce technology transfers, retaliate against sanctions, or influence political matters.

China has demonstrated its willingness to use market share as a foreign policy tool through its export control policies on critical raw materials. For instance, in July 2023, China imposed export controls on gallium and germanium, essential for various high-tech applications. In October 2023 it imposed temporary controls on graphite items, and most recently in December 2024 they announced further critical mineral export controls. These actions highlight China's strategic use of its market dominance to exert pressure on other nations.

While this theory of harm may not be a standalone threat, it could be a side effect of on-shoring. China's decreasing dependence on the global semiconductor industry increases its leverage in international negotiations, potentially destabilizing existing power dynamics.

Cybersecurity Warfare

The final theory involves cybersecurity warfare, which is a threat that cannot be ignored despite the lack of public evidence. There have been allegations about Chinese hackers interfering with the semiconductor supply chain, yet there is little concrete proof. For instance, a Bloomberg report highlighted a security vulnerability due to an unidentified chip on motherboards that originated from China, though the company disputed the report's accuracy. The lack of evidence could stem from the fact that the hardware community is naturally reluctant to discuss these vulnerabilities in public, since many of these backdoors could be unpatchable as they are on a hardware level. However, the ramification of hardware vulnerabilities could be dire and deserve consideration.

State capacity

It is important to realize that the theories of harm only speculate on the intention of the Chinese government. The actual impact depends on its ability to execute. Therefore, to properly right size the challenges one must consider how effective the Chinese government is in directing the semiconductor industry.

One of the most touted examples of the Chinese government’s determination in semiconductors is the launch of the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, with almost $100 billion raised.

However, despite substantial investments in the semiconductor industry, China's capital allocation has been marred by inefficiencies and corruption. Reports indicate a disproportionate focus on short-term profiteering in secondary markets rather than nurturing long-term industry research and development.

According to 21st Century Business Herald, the first phase of the fund has entered its investment return stage, resulting in major share reductions for many A-share companies, including Sanan Optoelectronics (down 70% since 2021), Goke Microelectronics (down 80% since 2021), China Resources Microelectronics (down 60% since 2021), etc. This kind of short term profiting is highly contradictory to the claim that the Chinese government is throwing money at the problem and heavily subsidizing the industry without a concern for quick returns, it would appear that the China Chip Fund has been a state-sanctioned pump and dump scheme.

There’s also corruption, as high-level executives of the China Chip Fund, Wenwu Ding and Jun Lu are under investigation of corruption charges. Although there’s only circumstantial evidence, these executives likely were trying to profit from the IPO activities from its portfolio. For example, UNISOC planned for an IPO back in 2019 until it hit a snag when its major shareholder went bankrupt. Since then, the Chip Fund has been aggressively investing into UNISOC, owning 17.7% of UNISOC’s share from the Fund I and II activities. Following the announcement of the third fund, UNISOC immediately received a $4 billion investment, the only significant investment of that quarter. This move would appear to be a last-ditch effort to prepare the company for IPO.

Plan of Action

While there is no substantial backing to the dumping claim, China’s on-shoring strategy and the accompanying leverage it creates for China on the international stage warrant policy responses that hedge against these challenges. In particular, should China continue to decrease its manufacturing capacity available for foreign chip manufacturing demand, new trade partnerships must be forged. In addition, the cybersecurity threat, although currently theoretical, also requires proactive measures.

In summary, the U.S. should

Deepen partnership with India by continuing the CHIPS act in support of existing commercial partnerships as well as workforce education.

Tighten EDA export control either through total ban or mandating EDA cloud migration, as well as perform routine auditing of corporate structure.

Expand defense procurement vendors by making it more attractive to conduct business with the government through demand aggregation with defense startups, as well as continuing the conventional procurement restrictions such as ICT controls

Deepen Partnership with India

In the event of increased Chinese aggression or overcapacity dumping, it is essential to have a reliable partner. India, with its vast population and industrial capacity, could be a decisive factor. The U.S. should foster stronger partnerships with India rather than solely relying on existing allies or on-shoring production.

Onshoring semiconductor production to the United States presents certain challenges, including community opposition, stringent regulatory environments, and cultural clashes. Despite the recent good news of TSMC Arizona’s superior yield rate, the conflicts among workforce will continue to be a destabilizing factor that jeopardize the smooth operation and growth of the on-shoring initiative, as exemplified by the recent class action lawsuit filed by current and former employees of TSMC.

In addition, deepening the relationship with India also helps smooth over the collateral damage caused by the exports control policy. For instance, under U.S. guidance ASML has instructed American employees to cease collaboration with Chinese customers in response to U.S. export restrictions. However, Dutch and Japanese engineers continue to service many machines in China, much to the frustration of their American counterparts. ASML reports that China accounts for 49% of its Q1 total sales and 20% of its backlog orders, underscoring the complexity of decoupling from the Chinese market. In other words, policy actions such as export control erodes the interest and goodwill of U.S. allies. Therefore, rather than jeopardizing the U.S. 's relationship with existing alliances, it is prudent to expand and nurture new partnerships.

U.S. companies are generally reluctant to invest heavily in mature nodes, given that advanced nodes such as 2nm and 3nm processes can command prices ranging from $20,000 to $50,000 per wafer, compared to just a few hundred dollars per wafer for legacy chip nodes. Collaborating with countries like India allows the U.S. to concentrate on developing cutting-edge semiconductor technologies while leveraging India's growing industrial capabilities to meet global demand for legacy chips.

Current U.S.-India partnerships include

Micron Tech's $825 million plan for a chip packaging and testing facility

Lam Research's plan to train 60,000 Indian engineers

Applied Materials' $400 million investment in semiconductor manufacturing equipment 5. AMD’s plan to build its largest design center in India.

Beyond these ongoing partnerships, the $200 million CHIPS for America Workforce Education fund could create joint curriculum development, student exchanges, and workforce development initiatives, including skilled trades essential for building and operating semiconductor fabs.

At the time of writing (June 2024), this proposal initially recommended that the U.S. Chips International Technology Security and Innovation Fund could direct more investment towards India to build semiconductor capacity and workforce, which has now been officially announced. The announcement is a vote of confidence for the idea of deeper partnership with India, and this direction should be carried through by the next administration.

Learning from the previous chip war with Japan, preferential treatment to allies like India, such as beneficial tax treatment for future chip exports, could be highly effective. This approach not only strengthens bilateral relations but also builds a robust semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem in India, reducing global dependence on China.

Export Control

Strengthening export controls, particularly around EDA tools where the U.S. controls 90% of the global market, is crucial. The existing EDA export control policy has several loopholes. Companies like Synopsys, Cadence, and Siemens have reported ways to tweak their EDA software to comply with restrictions and continue selling to Chinese engineers. For instance, Cadence is selling an EDA version that does not contain the GAAFET feature that’s required for cutting edge chips, which means Chinese companies still have access to EDA tools for the mature node designs.

To address these issues, the U.S. government can start by patching the loophole by banning all EDA software export to China and moving EDA software to cloud service providers based in the U.S. to facilitate more effective enforcement and revocation of access. In addition, the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) can mandate that the licenses for EDA export are only granted if the software is provisioned through cloud services.

Beyond export control policy, routine auditing of joint ventures for any ties to Chinese companies is recommended as well since given precedents of Chinese companies trying to circumvent the license control by partnering up with a non-listed entity.

Defense Procurement

According to the "Assessment of the Status of the Microelectronics Industrial Base in the United States," the U.S. lacks visibility into China-based dependencies in the defense industrial base. Addressing this requires conventional ICTS controls, Treasury SDN sanctions, and procurement restrictions for organizations critical to national security through initiatives like the Trusted Foundry Program.

Additionally, increasing transparency and traceability in the defense supply chain is essential. Implementing stringent requirements for suppliers to disclose their sources of semiconductors and other critical components can help identify and mitigate dependencies on Chinese products. Investing in domestic semiconductor manufacturing capabilities for defense applications can further reduce reliance on foreign suppliers. For instance, the most trusted foundry in the Trusted Foundry Program is GlobalFoundry, a UAE corporation. While the UAE has been historically an ally for the U.S., it has also become close to China in terms of trading activities, with a 40% rise in trade over the last decade. This tension creates a vulnerability in the Trusted Foundry Program as the U.S. is heavily indexed on a company located in a region heavily courted by China.

The difficulty to expand the Trusted Foundry Program network is partially caused by the lack of commercial justification for companies to go through the exercise. Commercial entities like Apple order far more chips than the Department of Defense (DoD), so it is often unattractive for foundries to jump through the hoops for government orders. One way to incentivize more participation in the program is increasing the volume of the government order.Given the recent rise of defense tech startups like Anduril, it is possible to group orders together since those chips will all be going to defense products. DoD’s Office of Strategic Capital should spearhead this initiative by surveying opportunities for demand aggregation with the top defense startup executives.

Conclusion

The rise of China's semiconductor industry presents multifaceted challenges that require a strategic and realistic response. Addressing these challenges involves strengthening export controls, enhancing defense procurement practices, fostering international partnerships, particularly with India, and increasing investment in R&D and workforce development. By implementing these policies, the United States can mitigate the risks associated with China's increasing dominance in the semiconductor industry while ensuring a stable and secure global supply chain.

Furthermore, proactive measures to address cybersecurity threats and promote transparency in the defense supply chain are essential to safeguard national security interests. Through collaborative efforts and strategic investments, the U.S. can maintain its technological leadership and build a resilient semiconductor ecosystem that supports economic growth and innovation.